As Andrea Cau puts it (after being garbled by Google Translate), many depictions of "feathered dinosaurs" don't actually depict "feathered dinosaurs" but "dinosaurs with feathers". They don't really show how these dinosaurs were feathered in life, but take a traditional scaly dinosaur and stick it in a suit of feathers. In other words, they're the equivalent of sticking a human into a gorilla suit and calling it a gorilla. I don't remember where I heard that analogy first, but it sounds apt to me.

|

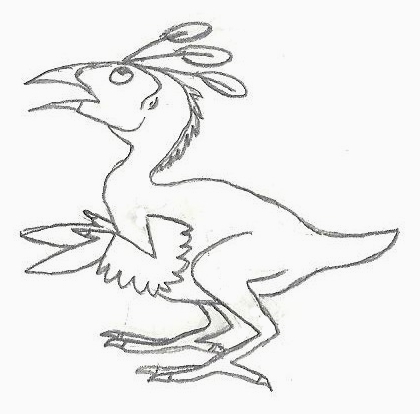

| This is supposed to be a chicken. |

It's not just non-avian maniraptors. Even the de facto "first bird" Archaeopteryx runs into this problem a lot. In reality, we have a decent amount of data on the plumage of these dinosaurs, and they certainly weren't scaly dinosaurs stuck in feathered suits. I briefly described in Part I what we presently know about the plumage of each non-avialian maniraptor for which evidence of feathers has been found. Incidentally, at least one thing I said in Part I is now probably outdated. I talked about how protofeathers, plumaceous feathers, and pennaceous feathers are all known in maniraptors. That is still true, but not in the way I described. A new study has shown that the feathers preserved in the feathered dinosaur specimens are likely more complex than typically thought. A (dead) European siskin was crushed in a printing press to simulate the preservation of the feathered dinosaur specimens, and it turned out that crushed pennaceous body feathers looked like plumaceous feathers or protofeathers. So the "protofeathers" and "plumaceous feathers" found on the bodies of oviraptorosaurs, deinonychosaurs, and basal avialians are likely actually pennaceous feathers, and the protofeathers in more basal maniraptors and other coelurosaurs are probably plumaceous feathers, or at least multiple filaments joined together at the base instead of single filaments. That leaves only the bristle-shaped EBFFs found in Beipiaosaurus (and possibly some undescribed basal coelurosaur taxa) as the only known monofilament feathers in maniraptors. Incidentally, the "ribbon-shaped" wing feathers reported in the juvenile Similicaudipteryx are likely just developing regular pennaceous feathers, while the ribbon-shaped tail feathers in many Mesozoic birds really are ribbon shaped, but the ribbon-shaped part is probably a specialized calamus instead of fused barbs as usually interpreted.

Several common and persistent characteristics of gorilla suit dinosaurs routinely find their way into reconstructions, even those that are otherwise perfectly accurate. Inaccurate wing feathers are one. All modern birds have a fairly uniform wing feather arrangement: tertials attaching to the humerus, secondaries attaching to the ulna, and primaries attaching to the second finger. Non-avian maniraptors and basal avialians don't appear to have had tertials, but aside from that all evidence so far shows that oviraptorosaurs and deinonychosaurs had a similar wing feather arrangement. Other than Caudipteryx zoui and the juveniles of Similicaudipteryx, all oviraptorosaurs and deinonychosaurs with preserved wing feathers have secondaries, and all, so far without exception, have primaries. (More basal maniraptors, such as therizinosaurs, didn't have actual wing feathers, just long protofeathers on the arms.) Possibly by far the most common error in depictions of plumage in oviraptorosaurs and deinonychosaurs is the lack of primary feathers. Although some speculate that certain taxa might have lost the primary feathers, this is typical wishful thinking. There is no evidence that this was the case. Even in flightless birds with short, stubby forelimbs, primary feathers remain, though they aren't easy to see because they "blend in" with the body feathers. Nor is there any reason to suppose that wing feathers would have gotten in the way of catching prey, as the palms and claws of theropods do not point the same way as the feathers do. On a related note, there is no evidence that the fingers of deinonychosaurs were scaly, even though just about everyone reconstructs them that way. As far as we know, even the fingers of deinonychosaurs were fuzzy, although oviraptorosaurs on the other hand appear to have had scales or naked skin on their fingers.

Another common error in reconstructions of feathered dinosaurs is stopping the head feathers at the snout, or worse, having scaly, lizard-like heads. Most of these reconstructions are evidently inspired by the fact that in modern birds, feathers stop at the snout. However, modern birds have beaks. In beakless maniraptors (including many Mesozoic birds), the feathers appear to go all the way down the snout, leaving only some naked skin at the tip. Of course, there are variations on this. Beipiaosaurus appears to have had a naked face, and many modern bird clades have evolved naked faces. Even so, there is no reason think that any maniraptor re-evolved scales on previously feathered parts of the body, even if they might have secondarily lost their facial feathers. By the way, although it is common to speculate that carnivorous non-avian maniraptors had bald heads, this appears to be based on vultures, and as I discussed briefly in Part V, bald heads in vultures have more to do with soaring habits than with feeding behavior.

| Fossil of Eoenantiornis buhleri showing feathered snout photographed by Laikayiu, from Wikipedia. |

Finally, in paleo art, it's common practice to "show all work" and make sure all the skeletal features and proportions of a dinosaur can been seen in reconstructions. However, as Matt Martyniuk, Mickey Mortimer, and Dr. Darren Naish discuss in the comments here, restoring feathered dinosaurs means "obscuring your research". Just look at how much feathers can cover up skeletal features in modern birds! Fossils of non-avian maniraptors also show obscuring of skeletal features by plumage. (Take a look at the fossils of "Dave" or Beipiaosaurus I posted back in Part I.) Even in featherless dinosaurs, the presence of soft tissues would mean that they were far from the shrink-wrapped creatures commonly depicted in art.

|

| Museum mount of Strix nebulosa showing extent of plumage, photographed by FunkMonk, from Wikipedia. |

do you think tyrannosaurids lost feathers when they reach adulthood or grew them in.

ReplyDeleteI can accept tyrannosaurids having more feathers as juveniles than as adults. I don't really buy a shift from completely feathered juvenile to completely scaly adult, though. If the juvies had feathers, I would guess that the adults would've still had at least some feathers, even if just a vestigial covering, or at the very least naked skin. (And, in fact, we know of naked skin impressions from Gorgosaurus.)

ReplyDeleteIf you do, don't you think Ornithomimus is an evidence of how the Coelurosauria (at least those basal) the plumage of adults is even more developed than that of juveniles?

Delete- Darla K. Zelenitsky, François Therrien, Gregory M. Erickson, Christopher L. DeBuhr, Yoshitsugu Kobayashi, David A. Eberth, and Frank Hadfield (2012) Feathered Non-Avian Dinosaurs from North America Provide Insight into Wing Origins. Science 338(6106): 510-514 -

That was a great find, though I don't think it necessarily has any new implications for ontogenetic change in tyrannosaurid feathers. The type of change that Ornithomimus/Dromiceiomimus demonstrates is significant in that it's unknown in other coelurosaurs, but the fact that feathers are more developed in adults has always been known (e.g.: in modern birds).

Delete(following comment is by google translate):

DeleteI agree with you, but I still think that there might have been a reversal ontogenetic somewhere in Maniraptora concerning the plumage. I think this because in addition to Ornithomimus we also have evidence of Jianchangosaurus (Therizinosauria, a more derived clade then Ornithomimosauria) with traces of carbonic plumage slightly longer than that of IVPP V11559's EBFF. And while Beipiaosaurus is known for adult specimens, Jianchangosaurus is ontogenetically immature. Mine is just a guess, but I think it's possible that basal Maniraptoriformes had ontogenetic development of the plumage reverse to that of those evolved (such as birds). And since Tyrannosauroidea is a clade just outside Maniraptoriformes, I assume that they also had a development of the plumage reverse to the avian one.

*I meant PROPORTIONALLY, not slightly.

DeleteI'm not particularly convinced there. A simpler explanation could be that Jianchangosaurus had longer EBFFs than Beipiaosaurus (or individual variation if they're the same thing). But ultimately more specimens are required to support or falsify the hypothesis.

DeleteOk. It was only a my guess, anyway :-)

Deletedeinonychosaurs babies were helpless or mobile

ReplyDeleteYoung deinonychosaurs appear to have been able to run around after hatching, so they were precocial.

ReplyDeleteGood article. Can you give us the Senter 2006 reference please?

ReplyDeleteThanks. The full reference is Senter, P. (2006). "Comparison of Forelimb Function Between Deinonychus And Bambiraptor (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26 (4): 897–906.

ReplyDeleteI will probably go and edit all these older posts with full citations when I have time.

Here is another example on how fluffy these animals could be (http://imageshack.us/photo/my-images/684/feathersorientation.jpg/) while it is probably true for a lot of species that they are very fluffy in live but sometimes it also depends on whether their feathers are puffed out or not. See how the outline changes on the Song Sparrow, you can probably see the outline of the body quite well when the feathers are down (part of the body was obscure by the wings of course) and if this is an example of a heron than you would probably see the rough outline of the neck vertebrae as well. So what I'm trying to say is it isn't necessary wrong even if a drawing doesn't go as far as what is suggested in your example.

ReplyDeleteAs for the pronation query you probably should also check this reference out:

Gishlick, A.D. (2001). "The function of the manus and forelimb of Deinonychus antirrhopus and its importance for the origin of avian flight". In Gauthier, J. and Gall, L.F.. New Perspectives on the Origin and Early Evolution of Birds. New Haven: Yale Peabody Museum. pp. 301–318.

Oh yes, plumage thickness varies even among modern birds and whether the feathers are puffed up or not. I don't intend to imply that all feathered dinosaurs should be depicted as extreme as the owl above, just that we probably wouldn't see all the body contours of Mesozoic feathered dinosaurs as sharply defined as it often is in art.

DeleteThanks for the ref!

And one more thing with the feather preservation is that under normal circumstances when a bird dies its skin tends to get dehydrated so very often their feathers puffed up due to the shrinkage of its skin (such as http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_thbRorvScz4/TLSy_-p3jAI/AAAAAAAACTo/JIeHEE4lOJ8/s1600/dead-bird.jpg, http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_thbRorvScz4/TL81y4k8AuI/AAAAAAAACUY/yRpjyo8lB80/s1600/dead_bird_blue.jpg, http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_GNeVEvZ8TmU/Soqgd72krKI/AAAAAAAABZo/ARrjuxu9w3s/s1600-h/RotBird.jpg and also this http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_thbRorvScz4/TEi3TW4m5uI/AAAAAAAACKM/wBUnqlGdL2Q/s1600/dead-bird-2.JPG). And for this reason, fossilized integuments on dinosaurs would tend to give the illusion of the animal being slightly more fluffier in life as well.

ReplyDeleteBefore I forget, I would also like to ask what actually constitute a tertial feather and do they have to be vaned or asymmetrical? If the answer is just any feathers attached to the humerus, then we do have evidence of tertial on these animals like Archaeopteryx (WDC-CSG-100) and these feathers are more like contour feathers.

That's certainly a good point as well, and something I'd probably mention if I were to update this post. (I don't usually update old blog posts though.)

DeleteBy tertial here I mean essentially full-blown flight feathers. I'm aware that shorter feathers on the humerus are indeed known for non-pygostylian maniraptors.

The reason I ask is because in Wellnhofer's book "Archaeopteryx the icon of evolution" he mentioned the following passage "...exact number of secondaries cannot be counted,... Marked, fuzzy furrows at the elbow joint may stem from the tertiaies..." about the Thermopolis specimen (WDC-CSG-100). It is clear that these feathers are more like semiplumes (my bad in saying contour feathers from my previous post) rather than proper remiges but they are regarded as possible "tertiaies" also. So when you were talking about (...Non-avian maniraptors and basal avialians don't appear to have had tertials...) the lack of tertiaies in these animals I just found it odd. I'm not sure what else could you have called these humeral feathers that trail along the posterior margin of the wings...

ReplyDeleteYeah, it's quite an old post. Unfortunately I just come across it today... (Sorry I'm a bit late...)

No worries. I would probably clarify "tertials" to mean "flight feathers" in the future, as that appeared to be what was meant when I first read that Archaeopteryx lacked "tertials" (e.g.: by Scott Hartman http://dml.cmnh.org/2010Nov/msg00183.html). Not sure what term, if anything, one should use when referring to the non-flight humeral feathers either.

DeleteI just had a quick look at Scott's Archaeopteryx Thermopolis specimen SVP 2007 poster. The kind of tertials that he was referring to is just plain pennaceous feathers which could be flight feathers (remiges) or even contour feathers. Perhaps you could use the term "non-pennaceous" feathers in your future posts to describe these humeral feathers.

DeleteI see. Though as I note in this post, the seemingly simple body feathers of non-pygostylian aviremigians may well be crushed pennaceous feathers after all, so "non pennaceous" might not be the best way to refer to them.

DeleteI was under the impression that the DML post is based on his (Scott's) SVP poster and in his own words on the poster he said "...the integumentary structures proximal to the elbow are clearly distinguishable from the pennaceous feather impressions of the distal forelimbs... in contrast, the elements associated with the humeri were made by thinner,more flexible structures that lacked a barb and rachis morphology... consistent with both plumulaceous feathers and a more primitive "fur-like"...". The poster pretty much implies that these are just non-pennaceous feathers. It is rather unusual if these humeri feathers on the WDC-CSG-100 are crushed pennaceous feathers since proper pennaceous feathers are also found with the same specimen especially in very close proximity. Take a look at the specimen and you'll see what I mean (the texture between these feathers are different). If you don't like the term "non-pennaceous" perhaps you can also use plumulaceous or even "fur-like"... since at the moment that is what they are.

DeleteI'm still somewhat doubtful as the study on crushed feathers referenced in this post was published online in 2011, so unless Scott knew about the results of the study in 2007 or came to the same conclusion as it, it might have simply been assumed that the humeral feathers were non pennaceous due to their different preserved texture. That study also showed that crushed body feathers are essentially indistinguishable from most of the supposedly simpler feathers preserved on fossils. However, you bring up a good point regarding the proximity of the humeral feathers to definitely pennaceous feathers. Plumaceous feathers sounds like a safe bet.

DeleteI don't have Foth's paper so I can't comment on it (only able to find the abstract). But all that I was saying is Scott referred these humeral feathers as non-pennaceous feathers (even in his DML 2010 post form your link, he was using the term "dinofuzz" for these unbranched structures). Since that was what you were referring to at the beginning "...I would probably clarify "tertials" to mean "flight feathers" in the future, as that appeared to be what was meant when I first read that Archaeopteryx lacked "tertials" (e.g.: by Scott Hartman http://dml.cmnh.org/2010Nov/msg00183.html)...". My post wasn't trying to convince or persuade you whether these feathers should be pennaceous or not but merely pointing out that you might have misinterpreted what Scott was saying in that particular post.

DeleteThe early bird catches the worm.

ReplyDeleteThe early chicken catches the seed?

Nice work on the (early looking) chicken.

ReplyDeleteIs it supposed to be a today chicken or early chicken??

It is a modern chicken, but not a serious drawing of one. It is meant to make fun of the way many extinct feathered dinosaurs are commonly (but incorrectly) drawn by drawing a chicken in the same way.

Delete