Those who read my lowly blog will no doubt be familiar with the work of Matt Martyniuk. As an incredibly talented paleoartist, Matt's restorations of prehistoric life are both aesthetically appealing and meticulously researched. In particular, he specializes in (and is probably best known for) depicting Mesozoic birds (=Aviremigia in his personally preferred usage). Additionally, he is a founding member of WikiProject Dinosaurs, a collaborative project that aims to increase the quality of Wikipedia dinosaur articles, and is single-handedly responsible for many of the life restorations and (especially) iconic scale charts present on the online encyclopedia.

One of the greatest contributors to the excellence of Matt's paleoart is the sheer thought and research that has been put into them. Many of the posts on his blog, DinoGoss, discuss aspects of paleoart that are frequently glossed over and yet immensely crucial to the field, such as the processes and biological significance behind feather colors. For this reason I have long thought that it would be magnificent if Matt wrote a self-illustrated book on restoring Mesozoic birds.

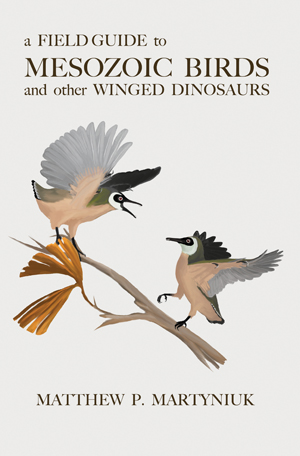

As it turns out, he did. About a month ago he teased us all with a picture of the following book cover on Facebook, and later wrote a more extensive article about the subject on DinoGoss.

The book is now out. Having spent two years in the making (so that's why Matt hasn't uploaded much on his DeviantArt for a while), for most part the book does not disappoint. The first few sections of the book detail the evolution and diversity of Mesozoic birds as well as things to take into account when restoring them, some of these incorporating updated versions of DinoGoss posts. Being the very topics I'd hoped Matt would cover were he to write a book, I found these chapters highly enjoyable and they will doubtless serve as a useful guide to other paleoartists looking to illustrate Mesozoic avifauna. Longtime followers of Matt will likely be able to identify nods to his online interactions and activities. Case in point, in order to demonstrate how feathers can obscure skeletal features, Matt uses the deinonychosaurs Troodon and Saurornitholestes to show that even dinosaurs that are supposedly anatomically disparate may have been hard to distinguish in life were we armed only with skeletal characteristics for identification, the same genera Mickey Mortimer used as an example in a comment on DinoGoss.

The main bulk of the book is presented in, as the title implies, a field guide format. With two chapters on oviraptorosaurs, five on deinonychosaurs (and some phylogenetically ambiguous paravians), one on non-ornithothoracine avialans, four on enantiornithines, and five on Mesozoic euornithines, each preceded by a phylogeny indicating the likely positions of taxa discussed, this presents near-comprehensive coverage on the known extent of aviremigian variety in the Mesozoic. Life restorations of almost all known Mesozoic aviremigian species are present, often shown in multiple views, poses, and sometimes ontogenetic stages, each accompanied by a scale chart done in Matt's recognizable style. For a great many aviremigian species, especially avialans, these are likely the first time they have been seriously restored, much less in print. Ornithologically savvy readers will be able to identify choices in coloration inspired by modern birds, though none fall into the trap of being a direct ripoff of a modern species. The succinct but informative text (as is typical for a field guide) lays down the physical characteristics, habitat, and known natural history of each taxon. Much of this will be a great help for buffing up the descriptions in my own list of maniraptors, again particularly with respect to avialans. There are a few cases where I felt that certain interesting facts that could have been added were missing, like Sinornithosaurus being known to have been preyed on (or at least eaten) by the compsognathid Sinocalliopteryx, but such preferences delve into the subjective side of things. Species too fragmentary to be reliably restored are listed in an appendix at the end of the book.

The book is immensely up to date, including even the last aviremigian to be published prior to its launch (Shengjingornis) and incorporating new research on the number of covert layers present in basal aviremigians. A recent paper that heavily influences the content of the book but came out too late to be extensively incorporated was the description of wings in ornithomimosaurs. Though the wing feathers of these specimens are not directly preserved, the authors of the study suggest they were pennaceous, potentially making ornithomimosaurs (and thus all maniraptoriforms) aviremigians. Should this be the case, any subsequent editions or companion volumes to this book would have to include at least ornithomimosaurs, therizinosaurs, and alvarezsaurs in addition to the groups it already has. Commendably, this discovery does get acknowledged in the introductory chapters of the book, and either way this does not cheapen this guide's value. Science marches on is an inevitable acquaintance of the best of us, and the book remains an indispensable reference for the groups it has managed to include.

If there's anything that does remotely detract from this gem, it's the typos. While on the whole they don't hamper the usefulness of the book, typos are abundant enough to be noticeable, especially to paleo-savvy readers. Most of these are spelling errors, but the most glaring example is that Cryptovolans is incorrectly stated to hail from the Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur Park Formation in Alberta, Canada. More extensive proofreading could've considerably increased the quality in this regard.

A bibliography is available at the back of the book, which I approve of (the last reference listed even has quite a bit of tongue-in-cheek humor to it), though I do feel that even more references could have been included. For instance, Velociraptor being known to have scavenged was evidently based on Hone et al. (2010), and yet this paper was not listed as a source. There are also countless specimen description papers that must've been referenced in a project of this type but are not mentioned. Although creating an exhaustive bibliography may not have been the main purpose of this book, it does appear strange to me that only some of the references used were credited. This is arguably especially important for the unpublished tidbits that are brought up. For example, Tianyuraptor is said to have had long neck feathers based on an undescribed mid-sized dromaeosaurid that preserves this feature and may be a specimen of said taxon. Those who are aware of this specimen will know the source of this, but those who know Tianyuraptor only from its published description (based on a specimen that preserves no feathers at all) may well be confused by this information.

There are also a few unexplained omissions to the list of Mesozoic aviremigians. Borogovia, Pamparaptor, Shanag, Otogornis, and Longchengornis are neither included as field guide entries nor mentioned in the appendix (or anywhere else that would explain their truancy). Hesperonychus is also bizarrely absent, despite being namedropped in one of the introductory chapters. (Edit: And Alethoalaornis too. See comments for more on the situation with these MIA taxa; thanks for chiming in, Matt!)

These are but quibbles, outweighed immeasurably by the book's numerous finer points, and if this review appears to imply otherwise it is only because I hold this work to such high standards. This is a book I'd recommend to everyone with an interest in some of the most wonderful of all creatures (i.e.: birds) and easily deserves a place of its own among works of this genre.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Thanks for the review Albertonykus! Can't believe that Cryptovolans thing managed to slip past every read through of the book. I'll chalk it up to a very late stage rearrangemt of the Microraptorians. Hesperonychus was originally where Crypto is now, but I decided that it was too speculative to include about the same time I was reviewing Senters new opinion on Microraptorians diversity, so I essentially swapped them out but apparently neglected to add Hesper to the appendix. Something to correct in a future edition!

ReplyDeleteWeren't Borogovia and Pamparaptor omitted from the appendix because they are known only from leg elements and those bones don't provide sufficient info allow for a restoration of Borogovia and Pamparaptor in the flesh? How come Shanag was left out of the appendix?

ReplyDeleteEven if you do include Hesperonychus, Borogovia, Pamparaptor, and Shanag, a slightly modified printing of this book is better than just a brand new edition (on grounds of publication cost).

The appendix lists species that weren't complete enough to be restored, so even if Matt considered Borogovia and Pamparaptor too fragmentary, they still should've been in the appendix.

DeleteI see. It's okay if hesperonychus and shanag were left out of the book because those genera have been covered in Greg Paul's dinosaur field guide.

ReplyDeleteAs a side note, I'd be curious to see if Matt mentioned the history of Protoavis and the discovery of the Morrison troodontid "Lori" because Protoavis could be a peculiar flying reptile that mimicked early birds and "Lori" itself is the oldest Paravian from North America, predating Falcarius by 25 million years.

That may be, though as this book is intended to cover all Mesozoic winged dinosaurs they should've ideally been included regardless of coverage by other books. And I'd have liked to see Matt's take on them.

Delete"Protoavis" is mentioned in the avian evolution chapter. I can't find any references to "Lori", likely because it hasn't been published yet (though Koparion, known only from teeth at around the same time and place, is listed).

The oft ignored Palaeopteryx is a third paravian from the Morrison formation (assuming it, Lori, and Koparion are not some combination of synonyms).

DeleteFor the record, I have to admit that the fact those few taxa were left out of the appendix was a bit of an oversight. Hesperonychus and Shanag in particular were last-minute cuts from the main body of the book. Enantiornithean fans may notice Alethoalaornis is also missing--it's complete enough to restore, I just was unable to get my hands on the paper or any figures!

Does anyone have any record of Early Cretaceous birds in Europe? As far as I'm aware, Enaliornis and Iberomesornis are the only bonafide Early Cretaceous birds from Europe (Palaeocursornis and Eurolimnornis may or may not be avian; Benton et al., 1997). Also, the putative Cretaceous form Gallornis Lambrecht, 1931 has not been discussed since its original description as requires re-appraisal. Have any idea about why no genuine fossil birds have been found in Early Cretaceous Germany and France?

ReplyDeleteConcornis and Eoalulavis are also from the Early Cretaceous of Europe.

DeleteDoes the Guide note that Unquillosaurus is likely a carnosaur (or even mention the genus at all)?

ReplyDeleteSpinosegnosaurus77/SpongeBobFossilPants

Unquillosaurus isn't mentioned.

DeleteTo the list of great absent, as well as Borogovia, Pamparaptor, Shanag and Longchengornis, I would add especially YIXIANOSAURUS! The beauty is that on p. 57 it is present in the cladogram as a sister-taxon of Oviraptorosauria, but then no description is to be found in the following pages (and however Yixianosaurus is not as fragmented as Borogovia or Pamparaptor). Anyway, I love this book, or rather, I take this opportunity to thank Martyniuk for publishing it! I still have to get along with Albertonykus to the question of Tianyuraptor, I was confused too at first reading ...

ReplyDeleteAnother thing that intrigued me was the idea unenlagiine for Timimus. However, if you do a new re-release, Matthew, remember also to update the cladograms! (Scansoriopterygidae more basal than Eumaniraptora, Deinonychosauria is paraphyletic, Balaur is an avialan etc etc etc...)

I didn't bring up Yixianosaurus as Matt had already posted about it being cut out from the field guide on his blog. But yes, even without that it's rather clear that it was originally intended to be in there.

DeleteIs Pneumatoraptor included?

ReplyDeleteSpinosegnosaurus77/SpongeBobFossilPants

Yes, in the appendix.

DeleteAh, okay. It didn't show up when I looked for it with Google Books' Preview feature, so I wasn't sure if it was in there.

ReplyDeleteSpeaking of things that don't show up on Google Books, Mickey Mortimer states that Martyniuk uses a clade called Metatheropoda, but he doesn't say for what. What does he use it for, anyway?

Spinosegnosaurus77/SpongeBobFossilPants

It's used for a clade containing compsognathids and pennaraptors, excluding tyrannosauroids.

Delete