As mentioned in my previous post, I did not get to visit the Ménagerie at Jardin des plantes during the third day of IPC 2018. So on the fourth day of the conference, my labmate Juan Benito Moreno and I decided to skip out on the early afternoon talk sessions to see it. The Ménagerie is quite a small zoo; one can easily see all the exhibits in the space of two hours. (Though I went on a second solo visit on the fifth day after the conference concluded, just so I could obtain better images of some animals. This post contains photos from both trips.)

The Ménagerie is one of the oldest public zoos in the world. Being so small, exhibit space is accordingly restricted. To its credit, the Ménagerie mostly lacks very large-bodied animals, instead focusing on smaller and medium-sized species that can live more comfortably in the enclosures. In many cases, these species are relatively rare in captivity and have successfully bred at the zoo, so I would still consider the Ménagerie worth a visit despite its small size. There were nonetheless a few exhibits that I felt were too small for the inhabitants, with the primate and parrot enclosures being the main offenders.

On both visits I got good views of this red panda lying high up on its climbing frame.

Some lowland anoa. Bovid diversity was one of the highlights at the Ménagerie (though not being a bovid fan in particular, I didn't go to lengths to photograph all of them).

A white-naped crane.

A white-fronted woodpecker.

A snow leopard.

This Malayan tapir had one of the more spacious exhibits in the zoo.

Probably the greatest highlight to me personally was seeing these MacQueen's bustards. We got to see one of the males perform its unusual courtship display!

Above the bustards perched a European roller and a Eurasian hoopoe. Picocoracians unite!

Next door was the zoo nursery, in which the only inhabitant I could see was this young white-naped crane.

In the same building as the nursery was an exhibit for tree kangaroos and brush-tailed bettongs, though the tree kangaroos chose not to show themselves. I did see a bettong sleeping in a corner, but it wouldn't have made for a particularly photogenic shot. (You may be able to spot it in the photograph below if your eyes are keen.) Quite a few mice scurried about, probably taking advantage of the food and hiding spots available.

A pair of blue cranes.

Some bharal (also known as blue sheep), including a kid.

A great green macaw.

A palm-nut vulture. Unusually for a bird of prey, a large proportion of its diet consists of fruits.

A king vulture.

A red-headed vulture, one of several Asian vulture species experiencing alarming population declines, threatened by the use of the veterinary drug diclofenac.

A red-vented cockatoo.

A palm cockatoo.

A southern cassowary.

Some yellow-throated martens. These mustelids hunt in pairs and sometimes in small groups, allowing them to hunt relatively large prey such as young deer. The glare on the glass was strong that day...

Some great gray owls.

A tawny frogmouth. As you might infer from my IPC poster, this species is of particular interest to me...

Some yaks.

In a large walkthrough aviary there was this pair of demoiselle cranes. (One individual is partly concealed behind foliage here.)

Another inhabitant of the aviary, a red-billed blue magpie.

Another European roller. I feel that the oddity of coraciiforms is frequently understated. They are rainbow-colored predatory dinosaurs that nest in burrows.

A violet turaco, in honor of the recent discovery that the Eocene bird Foro was a stem-turaco.

A red-legged seriema. It shared its enclosure with squirrel monkeys. In paleontology circles, seriemas are known for having a retractable second toe (similar to dromaeosaurids) and for being the closest living relatives of phorusrhacids (terror birds).

The layout of the vivariums was particularly vintage-looking (though this is perhaps not apparent from my photos). One vivarium denizen was this Schneider's toad.

A garden fruit chafer.

A Nile crocodile.

A Weber's sailfin lizard, the smallest of the genus Hydrosaurus. (Still good-sized for a lizard.)

A red-breasted goose, which shared this exhibit with other anseriforms as well as with flamingos.

Some yellow mongooses.

An agouti.

Some Indian crested porcupines.

Some West Caucasian turs, an endangered species of wild goat.

A rock squirrel. I've seen this species in the wild back in the United States, but this is the first time I've seen a black individual.

Wednesday, July 18, 2018

Tuesday, July 17, 2018

French National Museum of Natural History

The location of IPC 2018 was well chosen, taking place essentially next door to the botanical garden Jardin des plantes. It is here that the main galleries of the French National Museum of Natural History (Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle) are found. (The museum is divided into several sites scattered throughout France, but most of the publicly accessible galleries are at Jardin des plantes, which is also considered to be the museum's original location.)

Our first taste of the museum was at the conference's cocktail dinatoire, hosted at the museum's Gallery of Evolution. This gallery is probably most famous for its parade of African animals. Here I decided to take a shot focusing on the pangolin (with bonus marabou stork).

Though there was a lot to see in the Gallery of Evolution, the halls were dimly lit for most part, making photography difficult. Hidden away in a corner was an exhibit dedicated to recently extinct animals, featuring this skeletal mount of a dodo.

Some frolicking platypuses. I've rarely seen taxidermied monotremes put in such dynamic poses.

One section of the marine-themed exhibits in the gallery was focused on narwhals.

In a separate gallery was a temporary exhibit showcasing the Tyrannosaurus specimen "Trix", the first original Tyrannosaurus specimen to be on display in France.

In the same hall as "Trix" was a statue of the father of vertebrate paleontology himself, Georges Cuvier. For some reason he is depicted using his index finger to carve a rift through Africa on a globe.

The dinatoire had given us a good taster of the museum, but it hadn't yet given us a chance to visit the legendary Gallery of Paleontology and Comparative Anatomy. So (as I mentioned previously) on the third day of the conference some of us went to check that out. Along the way we passed by this carousel of extinct and endangered animals, featuring an elephant bird, a glyptodont, a Meiolania, and Sivatherium among others.

This was the sight that greeted us when we entered the Gallery of Paleontology and Comparative Anatomy. I guarantee that it is ten thousand times more impressive in person than what this photo suggests. Calling it a literally mind-blowing experience would barely be an exaggeration. I feel like everyone in my party was struck speechless for a few moments.

There was a lot to take in. It would have been impossible to properly examine everything even if we had spent an entire day there (partly due to the quantity of specimens and partly because some of the specimens weren't situated in places conducive to viewing), but we gave it a good shot. Here is a skeleton of a juvenile gorilla.

The marsupial case featured a thylacine skeleton as its centerpiece.

A long-beaked echidna.

The mustelid case, featuring a juvenile ratel.

A giraffe mounted with its nuchal ligament.

Naturally, Daniel and I spent a long time staring at the bird skeletons. Here is a case full of sunbirds.

A pair of kagu.

A screamer. It took us a few moments to figure out what it was (the scientific name on the label was outdated), but the carpometacarpal spurs probably should have clued us in.

Spoonbills.

A pelican mounted with its throat pouch.

A manatee skull.

An ocean sunfish.

A two-toed sloth turning its head around.

A bowhead whale mounted with baleen.

A balcony halfway up the stairs gave us the chance to look at the comparative anatomy exhibits from above.

The next floor up were the vertebrate paleontology displays. Here are some limb bones of Cetiosaurus.

A Sarcosuchus.

An Arctocyon, one of many Paleocene mammals of uncertain affinities.

I was surprised to see a restoration of a fully feathered dromaeosaurid included on one of the exhibit signs.

The French specimen of Compsognathus. Though Compsognathus was formerly considered the smallest non-avian dinosaur, I can confirm that it's not that small. At about the size of a turkey, it's certainly larger than the likes of Mei and Parvicursor.

A cast of the smaller holotype of Compsognathus.

The type specimen of Mosasaurus!

Another floor up hosted the museum's invertebrate paleontology displays. It was cool to see the holotype of Meganeura, though my photos of it turned out subpar.

After the museum, Daniel and I were interested in going to the small zoo (Ménagerie du Jardin des plantes) nearby, but Antoine (being a palynologist) decided to give us a tour of the botanical attractions in the garden first. Of course, I couldn't resist being distracted by the first sign of animal activity.

A Metasequoia, well known to paleobotanists who work on the Late Cretaceous (and onward).

The greenhouses were impressive. One simulated a tropical forest environment and included a staircase the allowed visitors to experience the "forest canopy". Though it must be said that being in a "tropical forest" without hearing any animal calls whatsoever was mildly eerie.

Another greenhouse arranged its exhibits in a more phylogenetically-based sequence, starting out with mosses and lycopods.

Platycerium, an unusual fern.

Some fossils of bennettitaleans.

By the time we stopped looking at plants, the Ménagerie was on the verge of closing. I did, however, take some time away from the conference to visit it on the following day, and will be covering it in the next post.

Our first taste of the museum was at the conference's cocktail dinatoire, hosted at the museum's Gallery of Evolution. This gallery is probably most famous for its parade of African animals. Here I decided to take a shot focusing on the pangolin (with bonus marabou stork).

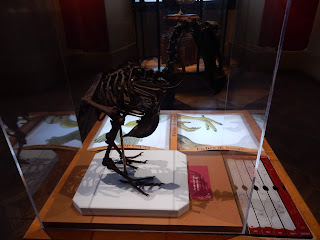

Though there was a lot to see in the Gallery of Evolution, the halls were dimly lit for most part, making photography difficult. Hidden away in a corner was an exhibit dedicated to recently extinct animals, featuring this skeletal mount of a dodo.

Some frolicking platypuses. I've rarely seen taxidermied monotremes put in such dynamic poses.

One section of the marine-themed exhibits in the gallery was focused on narwhals.

In a separate gallery was a temporary exhibit showcasing the Tyrannosaurus specimen "Trix", the first original Tyrannosaurus specimen to be on display in France.

In the same hall as "Trix" was a statue of the father of vertebrate paleontology himself, Georges Cuvier. For some reason he is depicted using his index finger to carve a rift through Africa on a globe.

The dinatoire had given us a good taster of the museum, but it hadn't yet given us a chance to visit the legendary Gallery of Paleontology and Comparative Anatomy. So (as I mentioned previously) on the third day of the conference some of us went to check that out. Along the way we passed by this carousel of extinct and endangered animals, featuring an elephant bird, a glyptodont, a Meiolania, and Sivatherium among others.

This was the sight that greeted us when we entered the Gallery of Paleontology and Comparative Anatomy. I guarantee that it is ten thousand times more impressive in person than what this photo suggests. Calling it a literally mind-blowing experience would barely be an exaggeration. I feel like everyone in my party was struck speechless for a few moments.

There was a lot to take in. It would have been impossible to properly examine everything even if we had spent an entire day there (partly due to the quantity of specimens and partly because some of the specimens weren't situated in places conducive to viewing), but we gave it a good shot. Here is a skeleton of a juvenile gorilla.

The marsupial case featured a thylacine skeleton as its centerpiece.

A long-beaked echidna.

The mustelid case, featuring a juvenile ratel.

A giraffe mounted with its nuchal ligament.

Naturally, Daniel and I spent a long time staring at the bird skeletons. Here is a case full of sunbirds.

A pair of kagu.

A screamer. It took us a few moments to figure out what it was (the scientific name on the label was outdated), but the carpometacarpal spurs probably should have clued us in.

Spoonbills.

A pelican mounted with its throat pouch.

A manatee skull.

An ocean sunfish.

A two-toed sloth turning its head around.

A bowhead whale mounted with baleen.

A balcony halfway up the stairs gave us the chance to look at the comparative anatomy exhibits from above.

The next floor up were the vertebrate paleontology displays. Here are some limb bones of Cetiosaurus.

A Sarcosuchus.

An Arctocyon, one of many Paleocene mammals of uncertain affinities.

I was surprised to see a restoration of a fully feathered dromaeosaurid included on one of the exhibit signs.

The French specimen of Compsognathus. Though Compsognathus was formerly considered the smallest non-avian dinosaur, I can confirm that it's not that small. At about the size of a turkey, it's certainly larger than the likes of Mei and Parvicursor.

A cast of the smaller holotype of Compsognathus.

The type specimen of Mosasaurus!

Another floor up hosted the museum's invertebrate paleontology displays. It was cool to see the holotype of Meganeura, though my photos of it turned out subpar.

After the museum, Daniel and I were interested in going to the small zoo (Ménagerie du Jardin des plantes) nearby, but Antoine (being a palynologist) decided to give us a tour of the botanical attractions in the garden first. Of course, I couldn't resist being distracted by the first sign of animal activity.

A Metasequoia, well known to paleobotanists who work on the Late Cretaceous (and onward).

The greenhouses were impressive. One simulated a tropical forest environment and included a staircase the allowed visitors to experience the "forest canopy". Though it must be said that being in a "tropical forest" without hearing any animal calls whatsoever was mildly eerie.

Another greenhouse arranged its exhibits in a more phylogenetically-based sequence, starting out with mosses and lycopods.

Platycerium, an unusual fern.

Some fossils of bennettitaleans.

By the time we stopped looking at plants, the Ménagerie was on the verge of closing. I did, however, take some time away from the conference to visit it on the following day, and will be covering it in the next post.

Labels:

Avialans,

Conference,

Shock horror a non maniraptor,

Trip

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)