The "new year" is not so new anymore (three new maniraptors have been named in 2021 already), but this is a tradition and I'm sticking to it, for now. Having done a sweeping overview of the past year in maniraptoran discoveries, I will now take a more in-depth look at the new extinct taxa that were described last year. In addition to the new genera and species of 2020, this time around I

will also make an effort to mention other relevant nomenclatural changes

that were proposed.

Alvarezsaurs

Last year saw the naming of Trierarchuncus, the youngest known alvarezsaur. Fragmentary alvarezsaur specimens had been previously reported from the latest Cretaceous Hell Creek and Lance Formations of the western United States, but these fossils had been left unnamed. Trierarchuncus itself is not known from a whole lot—it was described based on three thumb claws (belonging to three different individuals) from the Hell Creek Formation, and there are parts of an arm and a foot as well as a previously described partial hip that may also belong to it. Shortly after its initial description, a second paper assigned two more thumb claws to Trierarchuncus.

Even though the specimens don't represent much of the skeleton, Trierarchuncus is potentially quite informative about alvarezsaur biology. I noted last year in a post about alvarezsaurids that completely preserved alvarezsaurid thumb claws are rare. One of the claws assigned to Trierarchuncus, however, is very complete, showing a sharp tip and stronger curvature than is typically assumed for alvarezsaurid thumb claws. To my eye at least, this claw shape is in keeping with use of the claw in hook-and-pull digging, as I had contended in my blog post (and others had contended in scientific papers). Perhaps in reference to the strongly curved claw, the name Trierarchuncus can be translated as "Captain Hook".

Seeing as the claws assigned to Trierarchuncus come from individuals of different sizes, they may also provide insight into how alvarezsaurid claws changed as they grew. The larger Trierarchuncus claws are widened at their base and the surface of the bone exhibits a roughened texture, which likely developed as a response to considerable stresses. The authors who made these observations noted that this is also consistent with the hypothesis that alvarezsaurids used their thumb claws for digging.

Oviraptorosaurs

One of the most spectacular new maniraptors from last year, in terms of the fossil material represented, may have been the oviraptorid Oksoko from the Late Cretaceous Nemegt Formation of Mongolia. It is known from the skeletons of several individuals, including nearly complete skeletons. Notably among these specimens is an assemblage of at least three (maybe four) juveniles preserved together, which had been confiscated from fossil poachers in 2006. Some of these juveniles are preserved in lifelike crouched postures, suggesting that they had been buried rapidly and simultaneously. They therefore provide strong evidence of gregarious behavior in oviraptorosaurs. Oksoko was unusual among oviraptorosaurs in that its third finger was highly reduced, giving it functionally two-fingered hands, and the describers note that similar hands may have been present in Heyuannia huangi.

|

Several juvenile specimens of Oksoko (including the holotype, marked in blue) preserved together, from Funston et al. (2020).

|

2020 also saw a much-needed taxonomic overhaul of the caenagnathid oviraptorosaurs from the Late Cretaceous Dinosaur Park Formation in Alberta. Many Dinosaur Park caenagnathids were named based on non-overlapping parts of the skeleton, which has naturally raised questions about whether they all really represent distinct species or not. Based on the examination of newly described, more complete specimens, as well as assessment of individual growth stage based on bone microstructure, this latest study concluded that there are probably three distinct caenagnathids known from the Dinosaur Park Formation: the large Caenagnathus, the medium-sized Chirostenotes, and the small, newly-named genus Citipes, which had formerly often been considered a species of either Chirostenotes or Leptorhynchos. Although not the main focus of the study, this paper additionally mentions that the Gobiraptor from the Nemegt Formation likely represents a juvenile of Conchoraptor, as had been hinted in the past.

Also in the world of oviraptorosaur taxonomy, the feather-preserving specimens of Similicaudipteryx were reassigned to Incisivosaurus (previously known only from a skull and partial neck vertebra).

Non-ornithothoracean Paravians

In contrast to 2019, which was conspicuously lacking in new dromaeosaurids, at least two new dromaeosaurids were described in 2020. One of these was the microraptorian Wulong from the Early Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of China, known from the exquisitely-preserved complete skeleton of an immature individual. Like Microraptor, Wulong had large feathers on its hindlimbs, and the specimen also preserves a single pair of elongated tail feathers at the tip of its tail.

The other new dromaeosaurid was Dineobellator, a mid-sized (Velociraptor-sized) dromaeosaurid from the Late Cretaceous Ojo Alamo Formation of the United States. It is known from a partial skeleton, and as in Velociraptor and Dakotaraptor, its ulna exhibits a series of bumps for the attachment of wing feathers along the forearm.

One new paravian that might be a dromaeosaurid was Overoraptor, known from a couple of partial skeletons from the Late Cretaceous Huincul Formation of Argentina. The phylogenetic analysis in the description of Overoraptor recovered it as a close relative of Rahonavis, a smaller, likely flight-capable paravian from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. The phylogenetic position of Rahonavis is controversial; it has been found as either an unenlagiine dromaeosaurid or an avialan in recent studies. This particular study found Overoraptor and Rahonavis as avialans, though the phylogenetic dataset used tends to find paravian relationships that are not strongly supported by other analyses, with microraptorians and unenlagiines outside of dromaeosaurids and instead being more closely related to modern birds. It would be interesting to see where Overoraptor turns up when included in other phylogenetic datasets.

Rounding out the long-tailed paravians of 2020 is Kompsornis, a Jeholornis-like avialan from the Jiufotang Formation. The taxonomy of the various Jeholornis-like avialans is debated, but the describers of Kompsornis argue that Shenzhouraptor, Jixiangornis, Jeholornis prima, Jeholornis palmapenis, and Jeholornis curvipes all represent distinct, valid taxa. This paper is also notably one of the few to address "Dalianraptor", a supposedly short-armed, long-tailed avialan. The authors confirm that the original specimen of "Dalianraptor" is likely a composite, and find no definitive features that distinguish it from other Jeholornis-like avialans.

Enantiornitheans

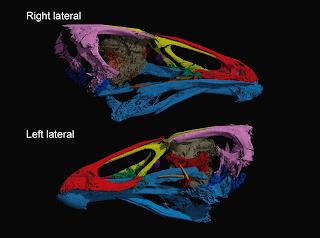

Only one new enantiornithean was named last year, but it was a doozy. Falcatakely from the Late Cretaceous Maevarano Formation of Madagascar is known from a nearly complete skull, and it's a skull unlike that of any other known theropod. Its snout was long and tall, giving it a superficial resemblance to a toucan or a hornbill. However, most of the snout was composed of enlarged maxilla bones, contrasting with the condition in modern birds, in which the snout is primarily composed of the premaxillae. The maxillae of Falcatakely were toothless and probably covered in a keratinous sheath, but the specimen preserves at least one small premaxillary tooth.

The describers of Falcatakely ran several different phylogenetic analyses and consistently recovered it as an enantiornithean each time. Even so, it's probably fair to wonder whether this bizarre creature really was an enantiornithean, especially considering that very few other Late Cretaceous enantiornithean skulls are known for comparison. As Mickey Mortimer has pointed out, a highly modified Late Cretaceous theropod with no obvious close relatives and known from limited remains is likely going to be difficult to place no matter what. (It's perhaps worthy of note that little to no skull material has been found for the two other paravians that have been named from the Maevarano Formation, Rahonavis and Vorona.) Regardless of what it turns out to be, the unusual and unexpected morphology of Falcatakely easily qualifies it as one of the highlights among last year's new dinosaurs.

In other news, a review of the Mesozoic and Paleocene pennaraptoran fossil record considered the poorly-studied Jiufotang enantiornitheans Largirostrornis and Longchengornis to be synonyms of Cathayornis, though this was not elaborated upon.

Non-neornithean Euornitheans

The taxonomy of yanornithid euornitheans was revised in 2020, resulting in the recognition of two new genera, Abitusavis and Similiyanornis. Similiyanornis from the Jiufotang Formation had a distinctive tooth arrangement in which the frontmost tooth in its lower jaw was enlarged. Abitusavis was larger than Similiyanornis and was discovered in the older Yixian Formation. Of note is that the first yanornithid specimen reported with fish remains preserved in its digestive tract (originally assigned to Yanornis) is now considered a specimen of Abitusavis. Several other previously described specimens (including the poorly-studied "Aberratiodontus") were deemed indeterminate yanornithids in this study, whereas Yanornis guozhangi was sunk into the type species of Yanornis, Y. martini.

Another new Early Cretaceous euornithean is Khinganornis from the Longjiang Formation of China. It is the first dinosaur to be described from this formation, and is known from a nearly complete skeleton, but its anatomical details are not well preserved. It appears to have been generally similar to the semi-aquatic euornitheans Gansus and Iteravis, and may have led a similar lifestyle.

Paleognaths

No new paleognaths were named last year (at least, none based on skeletal material), but the old genus Palaeostruthio was brought back and applied to "Struthio" karatheodoris, a large ostrich from the Miocene of Eurasia.

Galloanserans

Alright, let's do this one more time... Asteriornis from the Late Cretaceous Maastricht Formation of Western Europe is one of the few well-established examples of a Mesozoic crown bird. It is known from several bones, most notably a nearly complete skull. The skull exhibits features characteristic of both anseriforms and galliforms, and Asterornis may thus be a close approximation of what the ancestral galloanseran looked like. There's plenty more that could be said, but I already wrote about Asteriornis in more detail here.

The Cenozoic contributed its fair share of new galloanserans as well. From the Eocene of Kazakhstan came the anseriform Cousteauvia, known from a tarsometatarsus that displays features suggestive of diving behavior (hence the name honoring Jacques Cousteau). Its full binomial, Cousteauvia kustovia, is a bit of fun with homophones. There were also a couple of new pheasants from Bulgaria, the Miocene Phasianus bulgaricus and the Pleistocene Chauvireria bulgarica.

It's not often that we get a new gastornithid, but last year gave us Gastornis laurenti from the Eocene of France. It was named based on a distinctive lower jaw, but its describers mention that it is known from postcranial bones as well, which will be described in a later publication.

Columbimorphs

What's this? A fossil columbimorph older than the Pleistocene and represented by decently complete material?! Linxiavis was a sandgrouse from the Miocene Liushu Formation of China, and is known from a partial skeleton including most of the forelimbs. Sandgrouse today live in arid habitats (they famously use their belly feathers to transport water for their young), so the discovery of Linxiavis is consistent with other lines of evidence suggesting that the Liushu Formation was deposited in a relatively dry environment.

A new columbimorph that lived in more recent times is the Pleistocene–Holocene pigeon Tongoenas, remains of which are known from several islands in the Kingdom of Tonga. Its hindlimb anatomy suggests that it was a primarily tree-dwelling form, similar to the fruit doves and imperial pigeons that are still extant today. Tongoenas was one of the largest known flying pigeons, surpassed in that department only by the crowned pigeons, which can reach the size of a small turkey.

Gruiforms

The one new gruiform named last year was the coot Fulica montanei, known from a few tarsometatarsi found in the Pleistocene–Holocene Laguna de Tagua Tagua Formation of Chile. It was large for a coot, comparable in size to the extant horned coot (F. cornuta), and potentially had limited flight capabilities due to its size.

Meanwhile, to maintain consistency with the current taxonomy of extant cranes, the Pleistocene Cuban flightless crane "Grus" cubensis was transferred to the genus Antigone, which includes its probable close relatives such as the sarus (A. antigone) and sandhill (A. canadensis) cranes.

Charadriiforms

The origins of charadriiforms are murky, but 2020 saw the publication of a new taxon that may bear on the subject. That new taxon was Nahmavis from the Eocene Green River Formation of the United States, and it is known from a partial skeleton (missing the forelimbs and shoulder girdle) with preserved feathers. This specimen had previously been reported in popular books and websites as a potential close relative of the seriema-like bird Salmila from the Eocene of Germany, but the describers of Nahmavis instead find it to be more similar to possible stem-charadriiform Scandiavis from the Eocene of Denmark.

In the new study, Nahmavis and Scandiavis were indeed sometimes found as stem-charadriiforms. However, other analyses in this paper placed them as gruiforms instead. It is unfortunate that forelimb material is unknown for both Nahmavis and Scandiavis, seeing as the forelimb bones of charadriiforms are often distinctive. For what it's worth, playing around with the phylogenetic dataset used in this study, I've found that Nahmavis and Scandiavis are consistently recovered as stem-charadriiforms when the internal topology of crown charadriiforms is constrained to the results of molecular studies. In any case, the holotype of Nahmavis is a lovely specimen, and it's good to see it described at last.

Among crown charadriiforms, a new species described last year was the recently extinct sandpiper Prosobonia sauli from Henderson Island in the Pitcairn Islands. The genus Prosobonia also includes at least three other extinct sandpiper species as well as the extant Tuamotu sandpiper (P. parvirostris). Unlike typical sandpipers, the members of this genus are not migratory, and are confined to various remote Polynesian islands. Compared to the Tuamotu sandpiper, P. sauli had a wider, straighter bill tip and longer hindlimbs.

Natatoreans

As yet, it appears that no one has formally suggested in technical literature what name should be used for the clade uniting phaethontimorphs (tropicbirds, sunbitterns, and kagus) and aequornitheans ("core waterbirds", such as penguins, petrels, pelicans, etc.). I have provisionally settled on resurrecting the old name Natatores for this group, as it has been used in relatively recent literature for a very similar assemblage of birds.

Fossil penguins have generally had a good showing in recent years, and 2020 added Eudyptes atatu from the Pliocene Tangahoe Formation of New Zealand to the lineup. It is known from several specimens, and the holotype is a partial skeleton that includes much of the skull and shoulder girdle. E. atatu was closely related to the extant crested penguins, but its beak was shallower in depth compared to the fairly tall beak seen in the living members of this genus.

Two other new natatoreans belonged to a different group of wing-propelled divers, the extinct plotopterids, which were probably close relatives of boobies and cormorants. The new plotopterids Empeirodytes and Stenornis both come from the Oligocene of Japan and are known from isolated coracoids, with Stenornis being the larger of the two.

Telluravians

Whereas no raptorial telluravians were named in 2019, 2020 turned out to be extremely productive in the realm of new raptors. Two New World vultures were named from the Quaternary of Cuba, Coragyps seductus (which was similar to the extant black vulture, Coragyps atratus) and Cathartes emsliei (the smallest member of the genus Cathartes, which also includes the turkey vulture, C. aura, among others).

The Quaternary of Cuba gave us three new hawk species as well, these being Gigantohierax itchei, Buteogallus royi, and Buteo sanfelipensis. G. itchei was the biggest of the three (though it wasn't as big as the type species of Gigantohierax, G. suarezi), whereas B. sanfelipensis was the smallest, being somewhat smaller than a red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis). From further back in geologic time, we got the large Vinchinavis from the Miocene Toro Negro Formation of Argentina, represented by partial forearm bones. Even older was ?Palaeoplancus dammanni from the Eocene of the United States, known from a tarsometatarsus.

Arguably the most spectacular new accipitrid, however, was Aviraptor from the Oligocene of Poland. It wasn't spectacular due to its size—it was the smallest of the new accipitrids, about the same size as the aptly-named tiny hawk (Accipiter superciliosus). However, it is known from a nearly complete skeleton, a rarity among fossil accipitrids. Its combination of small body size and relatively long hindlimbs is commonly seen in extant accipitrids that hunt other birds, suggesting that it may have had similar habits. It may not be a coincidence that early hummingbirds and passeriforms are known to have lived in Europe at around the same time as Aviraptor.

The surge of new fossil raptors was not limited to vultures and hawks, as fossil owls had a very good year, too. There was the pygmy owl Glaucidium ireneae from the Pliocene–Pleistocene of South Africa, the oldest unambiguous member of its genus from Africa. The Quaternary of Cuba contributed the small barn owl Tyto maniola and the giant Ornimegalonyx ewingi, the latter based on specimens previously assigned to the horned owl Bubo osvaldoi. Although O. ewingi was much smaller than the type species of Ornimegalonyx, O. oteroi, it was still larger than any living owl species. The remaining species of Ornimegalonyx (O. acevedoi, O. gigas, and O. minor), however, have been sunk into O. oteroi.

Another large owl was Asio ecuadoriensis from the Pleistocene Cangagua Formation of Ecuador. Known from a couple of robust hindlimb bones, it was about the same size as a great horned owl (Bubo virginianus). Interestingly, its remains were found in association with the bones of smaller owls (and small mammals) that appear to have been etched by stomach acid, suggesting that it may have preyed on other owl species.

Numerous owls have been named from Paleogene fossil deposits, but most of these species are based on very limited material. Primoptynx from the Eocene Willwood Formation of the United States is known from a partial skeleton, making it one of the most completely known Paleogene owls. Like accipitrids, but unlike extant owls, Primoptynx had enlarged claws on its first and second toes, perhaps implying that it captured prey in a similar manner to accipitrids (maybe making use of the infamous "raptor prey restraint" method that may have also been employed by dromaeosaurids).

|

| Toes of Primoptynx, from Mayr et al. (2020). The claws on the first and second toes are particularly large. |

Moving away from raptors for a moment, Jacamatia from the Oligocene of France was a tiny piciform known from a partial wing skeleton. Its describers suggest that it was closely related to the jacamars and puffbirds, which are otherwise poorly represented in the fossil record. It may have belonged to the Sylphornithidae, a group of similarly tiny Paleogene piciforms, though very little overlapping material is available for comparison.

On the australavian side of Telluraves, we meet the small caracara Milvago diazfrancoi, yet another new raptor from the Quaternary of Cuba. The remaining new fossil australavians of 2020 were all songbirds: the corvid Corvus bragai from the Pliocene–Pleistocene of South Africa (the oldest known corvid from Africa) and the New World blackbirds Icterus turmalis and Molothrus resinosus from the Pleistocene Talara tar seeps of Peru.

Some additional revisions of note concerning fossil songbirds: the holotype of "Pliocalcarius" from the Pliocene of Central Asia, originally described as a longspur, was reinterpreted as a lark and transferred to the horned lark genus Eremophila, whereas "Eremophila" prealpestris from the Pleistocene of Bulgaria was argued to have been more similar to a different lark genus, Ammomanes, and removed from Eremophila.